Faith Today visited Uganda with Samaritan’s Purse to see the world’s worst refugee crisis — and how Uganda and partners are responding

The kids hang off tree branches, legs kicking and dangling, or mill around in clusters watching the strangers in their midst. They erupt in peals of laughter when they see their own picture on an iPhone screen.

The iPhone camera is the great icebreaker here, and the pictures also bring laughter to the women sitting on a batik cloth, weaving long, jet-black pieces of yarn into the hair of one of their friends – hair extensions in a makeshift salon in a makeshift community.

MAP: JANICE VAN ECK

MAP: JANICE VAN ECK

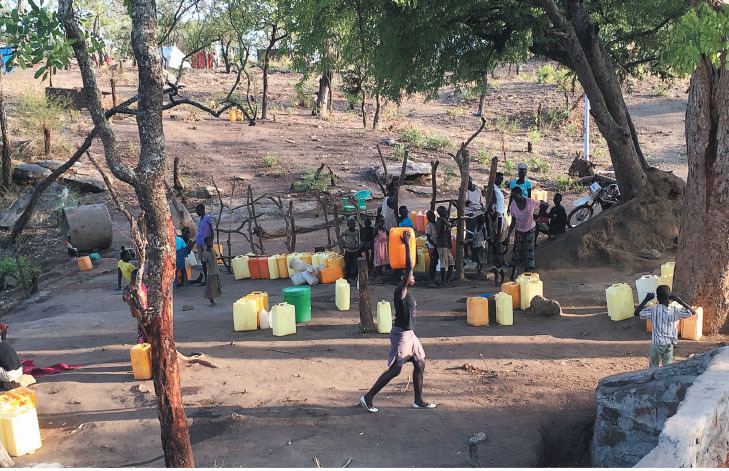

We are all grouped around a bore hole – a deep narrow well – at the Bidi Bidi refugee settlement in Northern Uganda. A line of faded orange and yellow jerry cans stretches across the ground waiting to be filled. Women take turns fetching part of their daily allotment of clean, fresh water.

This particular well was actually the first of 15 recently drilled in the largest refugee settlement in the world, to help with what the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has identified as the world’s fastest growing refugee crisis.

The UN estimates 4.26 million South Sudanese have been displaced, half internally and half fleeing to other countries such as Uganda (1 million), Sudan (416,000) and Ethiopia (382,000). The 15 new wells have been drilled by the hosts for our trip, Samaritan’s Purse Canada, a Christian relief organization based in Calgary and Boone, N.C.

Most of the refugees – you get that title when you flee for your life over an international border – walked for well over a week with a handful of belongings, their children and what food they could carry, often travelling in worn down flip-flops, the footwear of people with little choice.

Samaritan’s Purse distributes food rations in the settlements on behalf of the World Food Programme. Refugees are divided into groups of 30 or so, and then divide the supplies among themselves. PHOTO: KAREN STILLER

Samaritan’s Purse distributes food rations in the settlements on behalf of the World Food Programme. Refugees are divided into groups of 30 or so, and then divide the supplies among themselves. PHOTO: KAREN STILLER

Their former home was full of hope after a 2011 referendum when it separated from Sudan to become the world’s newest country. Now a civil war with multiple factions has dissolved their country under their feet.

So far 272,000 people have landed here in the West Nile region of northwestern Uganda, home to several refugee settlements where Samaritan’s Purse is at work digging wells and latrines, and distributing food, seeds and tools.

On a hill that overlooks the well stands Jane Janoba, 60. She’s a tall, still, barefoot figure on the packed dirt yard of her small plot of land. She arrived here in August after walking day and night for five days. She has agreed to be interviewed by the journalists visiting the settlement.

Jane Janoba cares for her grandchildren at the Bidi Bidi refugee settlement. PHOTO: KAREN STILLER

Jane Janoba cares for her grandchildren at the Bidi Bidi refugee settlement. PHOTO: KAREN STILLER

Someone asks if she likes it here. "You can sleep at night," she says. That says a lot. I think of my kids’ grandmothers and what they would need if their world was turned upside down.

I ask her if she has friends here. "I have friends in church," she answers. I’m glad. We smile at each other, just for a second. Jane has lost two adult children because of this conflict. One died and one disappeared when the war started.

"War ruins everything," says Dorothy DeVuyst, Samaritan Purse’s regional director for Africa. Conflict damages crops and destroys water supplies. It makes safe travel almost impossible. Neighbour is set against neighbour, and families tear apart. Fathers and sons are killed or recruited by force.

War makes rape a weapon of war, and this conflict in particular is known for its sexual violence against women. Countless women in this settlement have infants strapped to their backs in a swaddling cloth. There are charming babies everywhere you look. That doesn’t mean, of course, that all these beautiful, surprisingly quiet children were conceived from rape, but it’s likely some of them were.

These women, hauling water, lugging food, herding kids and braiding each other’s hair are creating a new life out of almost nothing. They are making a home out of a settlement.

It’s mostly women and children alone who make the hard journey. The UN reports women and children make up 86 per cent of the refugees trudging through bush, and hiding from rebels and government forces alike on their way through their war-wrecked country across the border to northern Uganda.

I speak with Viola, 20, sitting against the huge wheel of a parked truck that transports emergency food rations. Her baby is wrapped in a batik cloth and is peacefully asleep. Viola walked with her own mother to come here "because of the war," she says. Most people killed people there, she says. Here, in Uganda, she feels safe.

Uganda is practising a kind of rugged and expansive national hospitality that can make Canada’s decision to welcome 25,000 Syrians seem like a gesture, like inviting a neighbour over for tea instead of the entire street for supper.

Stephen Irumba works for Samaritan’s Purse in Uganda. He explains Uganda’s open and progressive refugee policy – no caps on numbers, open borders, small plots of government land given to families that make up these settlements (no one here calls them "camps"), and freedom to come and go – is part of the DNA of the Pearl of Africa, surrounded as it is by countries more often at war than not.

Irumba is proud to be Ugandan. You can tell. Uganda is in the thick of it, accustomed to welcoming troubled neighbours, a good host partly because they have not forgotten their own times of trouble (remember Idi Amin?). Some of Uganda’s current leadership grew up in refugee camps themselves, says Irumba, and have a heart for those going through the same thing.

Water and food distribution points also become places for the community to visit and support each other. Settlements can become like busy villages, with markets, churches and open air schools meeting under large, sheltering trees. PHOTOS: KAREN STILLER

Water and food distribution points also become places for the community to visit and support each other. Settlements can become like busy villages, with markets, churches and open air schools meeting under large, sheltering trees. PHOTOS: KAREN STILLER

Host communities receive some foreign aid as well. For example, if a Canadian charity provides health services to refugees here, local Ugandans can visit the doctor too. If a well is dug, everyone can draw clean water. If a school is provided, local kids can attend too. It’s both compassionate and strategic.

"The leaders of the current government were in exile. They know what is good for refugees," explains Irumba. "People at the top understand what it’s like to be a refugeeThey have open hearts. They protect them and they let them be."

Moses Agea is Samaritan’s Purse field manager for the Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement. "We would feel bad if they were stopping people. We have seen people who are suffering," he says. "Why would you stop people from coming if you have a godly heart?"

We drive, crammed into the back of a bouncing land cruiser, for almost an hour in search of the border with South Sudan. We want to witness a spot where families on the run cross from one country to another. We drive down one red clay, deeply rutted, grown-over road after another, with the odd miracle of pavement. Before we know we found it, we cross the border into South Sudan. There is a sagging rope tied between two trees with torn red and green rags dangling off it – a spot on the map called Pure. Somewhere on one side of the rope is civil war. On the other, a refugee crisis.

A paper stuck to a tree advertises a position with the Episcopal Church in South Sudan to work with adolescent girls who have dropped out of school. They are looking for a girl or woman who is a born-again Christian, and if you are married, you should not be pregnant or breastfeeding. Life and ministry go on, even in war.

Two young men hold old guns with chipped paint under a sagging shelter. They monitor this crossing and occasionally witness a weary family crossing from one side to another. They are perfectly pleasant, if a little perplexed, that we have shown up. They pose for pictures and let us roam around with our iPhones.

A family who has just crossed over rests under the shelter of a tree. After they catch their breath, their next stop will be to register at a refugee welcome centre, and then onto a bus to travel to one of the settlements and their new lives as UN refugees.

To understand the process families go through at the welcome centre, before they are settled, we walk the same path through a busy warren of tents and tables that 1,500 or so refugees walk on most days. It feels crowded and chaotic, and steaming hot. Green tarps strung overhead provide some shielding from the sun – and eerie lighting. Booths and tents of various charities form a kind of town square, offering what they are here to give. This is not a competition between charities, but more of a collaboration of compassion. Together the charities form a semicomprehensive response, "filling in the gaps," people here say, of the things the government can’t provide.

Refugees work their way through a warren of checkpoints and registration spots as they continue their journey to settlements. A group of refugees acted out some of what they had survived for a group of journalists brought to Uganda by Samaritan’s Purse. The settlements are filled with mothers and their children, many of whom lost their husbands, fathers and older sons to the conflict in South Sudan. PHOTOS: KAREN STILLER

Refugees work their way through a warren of checkpoints and registration spots as they continue their journey to settlements. A group of refugees acted out some of what they had survived for a group of journalists brought to Uganda by Samaritan’s Purse. The settlements are filled with mothers and their children, many of whom lost their husbands, fathers and older sons to the conflict in South Sudan. PHOTOS: KAREN STILLER

Register here, take this card and report in over there, have the circumference of your little guy’s arm measured to see if he is malnourished, there is where you get your vaccinations. Here is a wristband that will indicate if you are able bodied or all alone, or need extra help because of your special needs.

Later, things like a blanket, soap, one of those orange or yellow water containers and a mattress. And later still, a plot of land that can be up to 50 x 50 feet, room enough for a small garden to grow things like red tomatoes, purple eggplant and sckuma wiki – leafy greens we know as collard greens or kale that are a staple used to "stretch the week" of food supplies.

The gardens – depending on rainfall, of course – will stretch the World Food Programme food rations maintained and distributed by Samaritan’s Purse, who also provides the seeds, tools and training to give those gardens a better chance of flourishing.

Then we travel into a more established part of a settlement, to a group of refugees who have lived here awhile and have prepared for our visit. For them the welcome centre would be a dim memory. This settlement is now their temporary home.

The group of men, women, and children welcomes us with singing and dancing, and a kind of conga line snaking along, the shuffling feet from the tiniest to the largest moving in unison. We are escorted to a row of plastic chairs and invited to sit, watch and listen.

Alfred Modi, formerly a government administrator in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, welcomes our group and thanks Samaritan’s Purse, which he says has done "a wonderful job" digging wells and providing clean water to the settlement. Hooting and hollering ensues.

Then we are told the group has created a dramatic presentation to help us understand what they have been through.

A group of women stirs rocks in a tin pot and chats among themselves. A translator provides a somewhat unnecessary running commentary. "These women are cooking," he explains. A mock attack then breaks out, led by a particularly menacing man whose face is smeared with white. He wears a white lab coat and makes rat-a-tattat machine gun noises, wildly swinging his fake wooden gun.

One woman scoots around the scene, screaming with what seems like everything she’s got, and pulling a toddler with her who is terrified and sobs for real. A teenage boy pretends to slit the throat of a woman lying in the dirt, arms flung out behind her head. Then he walks away, pretending to lick clean the blade of the knife.

Back at the refugee welcome centre, Atite Monka, 25, stands under the sun, baby on her hip, in a long line with other women and their children. Her son is 17 months old and she carried him the whole way from South Sudan. The only other thing she seems to have is a cracked and faded brown leather wallet.

"We ate yesterday, but we haven’t eaten since," she says. "But the problems here are nothing compared to the problems at home." During her walk to Uganda, she tells me, "We walked over dead bodies. We saw the rebel soldiers, but they told us to go. We were just moving in the bush."

Our dream, she says, "is that we can stay here, peaceful, and that the situation is normalized in our country so we can go back."

I notice how worn out her wallet is and think that, if it were mine, I would throw it out. As we chat, it slips out of her hand and another woman in line picks it up and hands it back to her. The wallet must hold the commendation letter she tells me she has from the charity she worked for in South Sudan. She was a child protection officer.

I thank her for speaking with me. I tell her I’m going to write a story about all this. I wish her every blessing in the world. I turn away from her and leave her to the line.

Later, at the end of the day, I think about her again. She stays with me especially, I think, because of her perfect English, her adorable son and commendation letter that is so much proof of the life she left behind.

I imagine Atite making her way down a Toronto street, or maybe Halifax, a smaller, more manageable landscape. In my mind’s eye she walks down Barrington Street through that stretch where it gets very windy, and she is holding her son’s hand. He has plumped out and stretched up since arriving in Canada. He has friends.

Atite looks down a side road and notices the harbour sparkling in the sun, like it does on a certain kind of day. I imagine she is making her way to an event she has organized to help other newly arrived refugees, because she seems that sort of person, a woman with a plan and a heart and strong hands, capable. Atite and her son are safe, and happiness is coming.

My fantasy brings tears to my eyes. I know none of it will happen. Atite will be in a refugee settlement with her son, her wallet and commendation letter, for God only knows how long. What I really wish for Atite is what she wants – her own country returned to her in one piece, and she returned to it.

Karen Stiller of Ottawa is a senior editor at Faith Today. She visited Uganda for seven days in May 2017. In addition to the war-related crisis, South Sudan and neighbouring countries also faced famine this summer. Learn more at www.TheEFC.ca/Famine2017.